He was on his way to wash a car when he glanced up and saw co-workers sprinting off. A woman frantically motioned for him to flee. His heart raced as he tried to find the source of their alarm.

Confused and frightened, Javier Diaz Santana jumped over the wall behind the car wash in the San Gabriel Valley. Years earlier, a vehicle had run over Diaz’s foot while he worked there, and it was a struggle for him to run. He made it about a block. His foot throbbed with pain.

He saw two white SUVs on the street and realized what was unfolding. His workplace was being raided by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents, like so many other businesses and neighborhoods in Los Angeles over the past week.

Breathless, Diaz stopped. One of the vehicles pulled over, blocking his way. Masked, armed men exited, yelling. He tried to understand. He couldn’t see a badge. One had a vest with the letters “HSI” — Homeland Security Investigations, an arm within ICE.

One seemed to be demanding something. Diaz gestured at his ears.

He could not hear. And he couldn’t speak.

Javier Diaz Santana, left, communicates with his attorney as his brother Miguel looks on in downtown Los Angeles.

Diaz, 32, is deaf and mute. He thought that presenting his Real ID driver’s license would keep him safe. He has legal permission to be here. He came to the U.S. from Mexico when he was about 5 years old and had been granted permission to work more than a decade ago under the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. He has no criminal history.

He took his wallet from his pocket. An agent grabbed it and wouldn’t give it back.

Diaz took out his phone so he could type a message about his disability. They took that too. Then they cuffed his hands and shoved him into the SUV. He had no way to communicate.

“I was shocked at what was happening to me,” Diaz said through an American Sign Language interpreter. “I’m Mexican, I know you can tell I’m Mexican, but I don’t know what you’re catching me for. I was scared. I felt fear. What does that mean? I’m Mexican and you’re going to throw me out of the country?

“They just drove off, and I’m gone. There’s no communication,” he said. “I didn’t understand why.”

And so began a surreal near month Diaz never could have imagined taking place in the United States. He was sent to an immigration detention center in El Paso, where he spent weeks unable to communicate with his attorney or his family. At times, Diaz received paperwork in Spanish — a language he cannot read.

His experience raises serious questions, beyond whether people who are in this country with legal protection should be seized and detained by immigration agents. If ICE is going to apprehend people with disabilities, shouldn’t agents follow federal law and make the required accommodations available?

In a statement, an unidentified senior Department of Homeland Security official said medical staff provided Diaz “with a communications board and an American Sign Language interpreter.”

The statement ignored the fact that Diaz has DACA protection provided by the government. After the Times followed up again about that protection, a senior DHS official said in an email, “Deferred action does not confer any form of legal status in this country.”

“The facts are this individual is an illegal alien. This Administration is not going to ignore the rule of law,” the original statement read.

“The United States is offering illegal aliens $1,000 and a free flight to self-deport now,” DHS continued. “We encourage every person here illegally to take advantage of this offer and reserve the chance to come back to the U.S. the right legal way to live American dream. If not, you will be arrested and deported without a chance to return.”

In another case this month, a federal judge ruled that the government had to provide a Mongolian Sign Language interpreter to a deaf immigrant who has been detained in San Diego County since February. U.S. District Judge Dana Sabraw, a George W. Bush appointee, reportedly called it “common sense that a person has a right to communicate.”

Diaz was released July 8. He is one of an unknown number of immigrants with permission to live and work in the U.S. who have been caught in the dragnet of President Trump’s deportation campaign.

Diaz’s attorney, Roxana V. Muro, said she has another client who remains detained after being picked up outside a Home Depot despite showing his work permit.

“They really just don’t care if they have a work permit, if they have DACA, if they have (Temporary Protected Status) — they detain,” Muro said. “They’re just engaging in racial profiling. It’s nothing but that. They don’t care whether you stand and produce documents or run.”

Diaz, she said, “was working lawfully, doing everything right, everything he was supposed to be doing.”

Diaz arrived in the U.S. as a child. His parents had struggled to get him the services he needed in Mexico, they hoped he would have a better life here.

The family moved to South L.A., where Diaz, an older brother and his parents squeezed into a two-bedroom apartment with three relatives. They were fixtures in the complex. Neighbors became close friends, at times celebrating the New Year, birthdays and other holidays together.

Diaz thrived. He attended Marlton School, which specialized in teaching students from kindergarten through 12th grade who are deaf and hard of hearing. He ran track and was a right winger on the soccer team. He graduated in 2011.

His brother Miguel, who is nine years younger, attended the same school to learn ASL so the siblings could communicate. Diaz cannot read or write in Spanish and relies on Miguel, 23, to be his voice. Their mother knows some sign language; their father speaks in Spanish into Google Translate and then shows Diaz the English translation.

1. Javier Diaz Santana communicates with his lawyer through a sign language interpreter. 2. Attorney Roxana Muro, left, communicates with Diaz, center, at her office. 3. Diaz leaves his attorney’s office with his friend and co-worker Bryan.

Diaz came to the attention of immigration officials in 2013, when an asylum application was filed on his behalf. The application triggered removal proceedings.

But under the Obama administration, the federal government used a procedure called administrative closure to help clear immigration court backlog by temporarily removing some cases from the docket so resources could be focused on higher-priority cases.

Diaz’s case was administratively closed. At about the same time, he received DACA protection.

He was hired at the car wash in Temple City in 2020. He worked six days a week, hosing down cars, soaping them up and vacuuming inside. He loved that it was fast paced. His co-workers knew him as “el mudo,” the mute.

He built a community there. Sometimes he’d pack an extra ham sandwich to bring to his good friend and co-worker Bryan, who asked to only be identified by his first name because of his immigration case. Bryan did not use sign language, but the two formed their own method of communication. At the end of each shift, Bryan would twirl his fingers, his way of signaling to Diaz that he’d see him tomorrow.

Diaz was normally off Fridays. But on June 12, a Thursday, he’d gotten two flat tires and hadn’t been able to work his regular shift. His boss asked him if he could work the next day. So he went in.

Miguel Diaz Sr. outside the family’s apartment in South L.A.

That morning, everyone at the car wash was on high alert. They had heard ICE was in the area. News of raids had been circulating for a week.

Diaz noticed that fewer people had shown up to work when he started his shift about 8 a.m. His boss wrote a message asking if he was documented. Diaz wrote back that he had DACA protection.

A co-worker pointed out the white SUVs nearby. They told Diaz the vehicles belonged to ICE.

Diaz had just finished his 30-minute lunch break and was walking over to wash a car. Grainy surveillance footage reviewed by The Times captured what happened next.

Five people in blue work shirts bearing the car wash’s logo made a beeline for the wall and appeared to use a bench to jump over. Someone gestured for Diaz to run. He couldn’t hear the shouts of “migra.”

He walked a few steps, put a hand on his head, appearing confused. He jogged to the wall and pulled himself over, dropping out of sight.

After he landed, Diaz felt pain shoot through his foot. He scaled a few more walls in backyards before running out onto Sultana Avenue. Agents spotted him and blocked his path.

Diaz motioned that he couldn’t hear. The agents took his phone and cuffed his hands in front of him, tight enough to bruise. They did not explain why he was under arrest or say why he was being taken.

Neighbors hold signs to welcome home Javier Diaz Santana in South Los Angeles on July 9.

“I signal to them I can’t hear, and they just go ahead and cuff me. They’re very forceful,” he said. “They don’t care. They don’t care if you understand. They just cuffed me. There’s no explanation as to what’s going on, no one told me anything.”

He sat in the SUV. An officer showed Diaz his phone, where he had typed a question: What country are you from? Diaz couldn’t answer.

“I can’t sign with my hands cuffed,” Diaz said. “They took my power.”

When he was eventually transported to downtown L.A., he saw protesters and the National Guard. He was shackled around the waist and held in what he likened to a jail.

Diaz struggled to quantify how many others were waiting with him, saying “it was a lot more than I can think.” There were three big groups of people, he recalled.

Bryan was there, too. His friend gestured with his hands, trying to calm Diaz, who feared he wouldn’t hear his name called. Bryan gestured at his own ears, telling him that he was listening for him.

But then Bryan’s name was called, and he was moved into another room. He flagged down an officer and explained he was trying to help his friend, who cannot hear or speak.

“That has nothing to do with you,” he said the officer responded. He didn’t see Diaz again.

An agent with a badge around his neck approached Diaz, who motioned that he couldn’t hear. The agent wrote on a piece of paper in Spanish. He removed the cuffs and Diaz wrote back that he only knew English. Another agent asked Diaz when he entered the country.

“I don’t remember, I was a baby, I don’t know that story exactly,” he said. “I couldn’t give them those details.”

They asked if he had a green card. Diaz wrote no.

“I thought they were going to ask me, ‘Do you have DACA,’” he said. They never did.

He thought they would check his wallet. His mother had taken his current work authorization card, which expires in October, so she could help him renew his permit. But his license was there.

Diaz was finger printed and photographed, still in his work uniform. Inside the detention center, there was a bathroom, but no shower and no space to sleep.

Despite so many people around him, Diaz said, he felt alone.

1. Adeline, 1, and her grandmother Maria Diaz await the arrival of Diaz’s son Javier. 2. Maria Diaz shows a photograph of her son Javier in a court appearance while detained.

Diaz’s family was desperate to find him. His mother, Maria, had gotten a call from a relative telling her the car wash had been hit by ICE.

The family shared their locations on their phones, and Miguel zoomed in on his brother’s, the detention center in downtown L.A. Miguel grabbed Diaz’s work permit and headed there.

But he was turned away with no information. The family couldn’t find Diaz on the ICE locator.

Maria feared her middle son, a slight 5-foot-5, would be deported to Mexico, where he wouldn’t be able to read signs. Life was already hard there; what would it be like for Diaz, she wondered. He doesn’t know Mexican Sign Language.

“I’m never going to see him again,” Maria thought.

The family called Muro’s office that day and spoke with an assistant. The immigration firm was booked out with appointments two months in advance. But when the raids began, Muro instructed her staff to screen those detained to see if they could help or refer them out.

That evening, she learned of Diaz’s case. She called the family.

After learning Miguel had had no luck finding his brother downtown, Muro drove to an ICE office in San Bernardino. An officer in the parking lot gave her the phone number and email address for a supervisor at the B-18 detention center where Diaz was being held.

She called. It was around 7:30 p.m. No one answered. So she sent an email.

“Help DEAF MUTE CLIENT DETAINED WITH DACA,” the subject line read. She attached Diaz’s current work permit, which had been issued by U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Services.

“Since he had DACA, under any other period of time in my time practicing, this would have been somewhat easy,” Muro said. “You show up with the DACA approval notices and talk to a supervisor and I’m almost certain he would have been released.”

The supervisor responded, saying he would look into it.

By June 15, Diaz was on a plane to Texas. It was his first time flying.

He spent the trip in handcuffs.

Javier Diaz Santana wears an ankle monitor while reuniting with his family in South Los Angeles.

When Diaz arrived at a detention center in El Paso, he changed out of his work uniform and into a blue shirt and pants. Officers kept him in a cell by himself.

Diaz said he received pen and paper, on which he would ask to go to the bathroom. He had never felt more isolated. At times he cried and wondered if his family was crying too.

He spent most of the time sleeping, tossing and turning on the hard bunk bed. Sometimes he joined other detainees watching TV. There were no subtitles.

“Day would come and it was the same thing,” he recalled. “Morning, afternoon, evening, I was isolated.”

Diaz saw people who were scared. Like many, he prayed.

“For God to help me and to save me,” he said. “I just wanted to be safe.”

Although the ICE locator showed Diaz in El Paso, Muro struggled to find him, even when she provided the facility with his “alien registration number,” assigned to noncitizens. It wasn’t until she provided a variation of his name that they were able to track him down. She sent proof of Diaz’s DACA protection, but he remained detained.

Muro learned that the government in May had filed a motion to revive Diaz’s administratively closed case.

In recent months, Muro said she’s received 40 motions from the government that involved reopening administratively closed cases. At least one involved someone who was already granted lawful permanent residency. Diaz’s case, she said, had yet to be put back on the court calendar.

Muro tried to find a way to connect with Diaz as he was detained in Texas. The supervisor told her the facility did not have text telephone devices, used by people with hearing or speech disabilities to send and receive text messages.

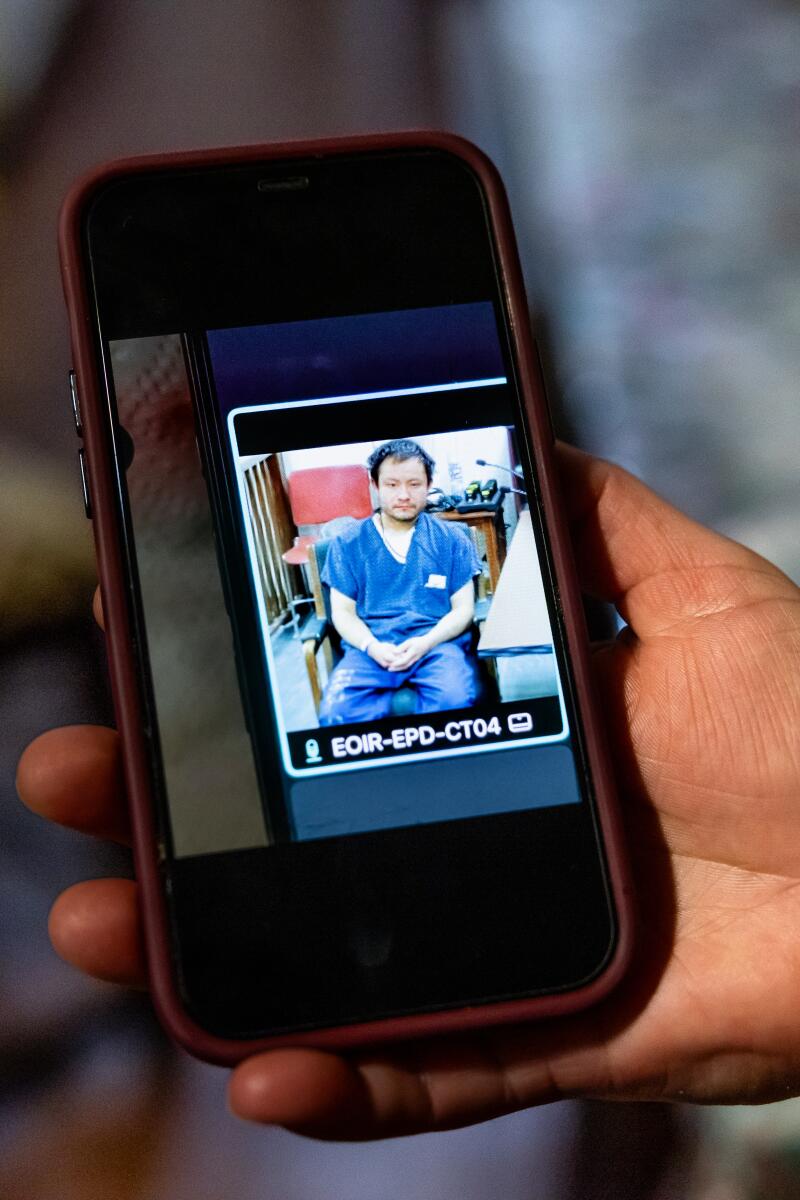

Muro saw her client for the first time on Webex at his bond hearing on July 2. During the hearing in El Paso, Diaz, hunched over, hair disheveled, turned toward the camera to watch an interpreter explain the proceedings.

He said it was the first time in weeks someone communicated with him using sign language. Other than acknowledging when the judge asked questions, Diaz kept his hands clasped in his lap.

Muro told the judge that Diaz’s removal case had been administratively closed in 2013. She said he has DACA protection, that it was just renewed and would not expire until 2027.

A Department of Homeland Security lawyer who sat at a table near Diaz said that an addendum in Diaz’s arrest record in Texas acknowledged that he had DACA. She added that Diaz’s case remained administratively closed, which appeared to puzzle the judge.

“I never have had that before, where I have a bond request on an admin closed case,” the judge said. “This is the first time.”

The government lawyer explained that Diaz had been picked up during “an at-large operation by ERO and HSI,” both arms of ICE. The judge questioned whether he even had jurisdiction to grant bond.

“You do have jurisdiction. He should not even be detained,” Muro said. “He was lawfully working at the Temple City Car Wash when ICE raided the car wash. I can discuss the illegal arrest later.”

The judge asked if Diaz had any criminal history. The government lawyer said no.

“There’s no evidence in the record that would suggest that you are a danger,” the judge told Diaz.

1. Javier Diaz Santana center, is welcomed home by neighbors. 2. Diaz receives a hug.

Muro told the judge her client was not a flight risk and had maintained his DACA over the years. The judge set bond at the minimum — $1,500.

He gave Homeland Security the discretion to monitor Diaz but said the agency was not required to do so.

“Good luck,” the judge told Diaz. “I hope that everything works out for you.”

The following day, Diaz was finally able to talk to Muro and his family. His mother cried. He felt like crying too.

His brother told him he would soon be released. Diaz asked if his brother had retrieved his car. Miguel assured him he had.

Someone had even scrawled a plea to traffic enforcement officers on the burgundy 2005 Toyota Camry: “The owner of this car was detained by ICE this morning. A hard working man working everyday at the carwash. I hope he is released or his family picks up his vehicle. Please don’t issue a ticket.”

On July 8, a Tuesday, an agent signaled Diaz to get up from his bed. He wrote to Diaz that his bond had been paid and he could leave. Twenty-five days had passed since his arrest. It was his mother’s birthday.

“Finally, I’m free,” he thought. But before he left, the officers put a black monitor on his left ankle.

Diaz didn’t know what the monitor was or why it had been attached to his ankle. The officers handed him a sheet of paper with instructions on the device. It was in Spanish.

Maria Diaz, center, speaks to her son Javier at home.

Miguel and a cousin bought flights to El Paso. Diaz waited in a shelter. When they came to pick him up, Miguel was given his brother’s belongings, including his wallet. The Real ID was no longer inside.

Expenses kept stacking up. They rented a hotel. Because they couldn’t fly without Diaz’s ID, Miguel scrambled to rent a car.

Miguel noticed a change in his brother, who often smiled and laughed, but now seemed reserved. Diaz would ask permission to eat. To use the restroom. To shower.

“I knew he had a fear,” Miguel said. “I think he felt he had to be a certain type of way.”

Diaz’s cousin and brother took turns driving the more than 11 hours back to L.A. Diaz anxiously checked the ankle monitor.

They passed through New Mexico. Then Arizona. Diaz, who had never before left the state of California, marveled at the $2 gas.

But he also realized that people noticed the ankle monitor. His heart raced.

“They didn’t call the police or anything, but I know they were looking at me,” he said.

He did not start to calm down until they reached California.

As night fell, Diaz’s father, Miguel Sr., clutched his phone outside the apartment, watching his son’s location draw nearer with each minute.

“Vienen en San Pedro,” Miguel Sr. announced. They were on a nearby street. And he still called his son to make sure they were almost home. “Ya mero llegas verdad?”

“Ya estoy en la esquina,” Miguel Jr. said. They were around the corner.

Javier Diaz Santana reunites with his mother, Maria, at their home in South Los Angeles.

As Diaz shuffled toward the stairs leading to his apartment, his father bounded down. He held a blue poster the neighbors had made. It read: “Welcome Home Javier.” Another poster delivered the same message, this time in sign language.

Diaz’s eyes were blank, his arms heavy at his sides.

Miguel Sr. embraced his son. Neighbors cried as they hugged the man they had known since he was a boy. They patted his hair, which had grown long in detention. He hiked up his pants leg to display the ankle monitor.

His mother was waiting in the hallway of their small apartment. He reached for her, hugged her tight.

As he wiped away her tears, his own threatened to spill over.

Finally, he was home.