Defining “Freedom to Read” Bills–What They Do and Don’t Do

In general, there are two types of anti-book ban bills being passed at the state level. The first ties a pool of money to libraries creating policies asserting that they will not ban books. That agreement may involve proving your library has a policy in place against book banning modeled after the American Library Association’s Freedom to Read statement or one that is more specific to the particular institution. If you have these things, you send proof to the designated official in the state, and you’ll receive a small grant to use for your library. In Illinois, those grants have ranged in the $800-$2000 range, which for many libraries, is a huge sum of money. This style of anti-book ban bill does not require compliance, and as reported by the Chicago Tribune, many places throughout the state have simply elected not to take the grant money. These bills can apply to public libraries only, to public school libraries only, or to both simultaneously, as each state legislates this differently.

The second type of anti-book ban bill strengthens librarian job protections. These bills codify that librarians, as part of their job, can deny book bans. They are the experts with the knowledge and resources to make developmentally—and community—appropriate collection decisions, and as such, when they defend a book’s inclusion in a library, their jobs will not be on the line. These bills are meant to encourage librarians to do the work. They’re a safety net for library workers who’ve been engaged in anti-censorship measures in their libraries. But like the other style of anti-book ban bill, these measures do not require librarians to do anything. Indeed, those already deeply engaged in quiet/silent censorship can continue unfettered. In some cases, such legislation further emboldens those who simply don’t purchase materials or inappropriately “weed” them because they can make the claim they’re doing the thing that’s best for their community (what they mean is they don’t want to do their jobs and are instead either in agreement with the complaints or are complying in advance).

Literary Activism

News you can use plus tips and tools for the fight against censorship and other bookish activism!

These two broad categories of anti-book ban bills can overlap. Politicians who draft or sponsor these bills do so with the knowledge of what has the best possibility of being approved, thus why each piece of legislation differs (and why sometimes, you’ll see several pieces of legislation addressing all of these parts).

But what each of these anti-book ban bills has in common is that they address one type of book censorship: the banning part. There are, however, Four Rs of book censorship, a term and classification coined by Dr. Emily Knox:

- Restriction, or the intentional inability for books to be accessed by all who may want them. This would be putting books behind a desk so that people must ask to borrow them and may be denied if they don’t meet certain requirements.

- Redaction, the intentional editing or removal of material from a work. Cy-Fair Independent School District (TX) did this when they elected to omit sections from textbooks to be used by students that they disagreed with. Another example would be drawing underwear on a character in a book who may be nude, as was done several times in libraries in the ’70s and ’80s with Maurice Sendak’s In The Night Kitchen.

- Relocation, the intentional moving of a book from one area of the library to another. This is what Greenville County Libraries (SC) did with their youth LGBTQ+ books. It’s what was going in at East Hamilton Public Library (IN) before the board returned to actually serving its community rather than a few religious zealots.

- Removal, also known as a book ban.

Anti-book ban bills only address that last R, the actual removal of books. That still leaves plenty of room for libraries to redact, restrict, and relocate materials, as well as engage in quiet/silent censorship. It’s not a complete end to book censorship, and because of how much latitude there is in what these bills require, so, too, is there plenty of room for continuing book bans even in states with these laws.*

None of this is meant to be a downer. It’s meant to be a reminder that “good” “blue” states passing these bills still don’t have good mechanisms for addressing the reality of book censorship. Just look at Anoka County, Minnesota, schools. It’s a “good” “blue” state with an anti-book ban law on the books, and yet, the district still plans to use the slapdash, partisan creation of Moms For Liberty, BookLooks, to make decisions on whether or not to keep materials on shelves. These bills are tied to incentives or to individual protections. They are not about protecting the institutions nor the broad scope of the problem. (In good news, the policy in Anoka County has been overturned and the district no longer relies on the shut-down BookLooks website to make collection decisions–that ended because of lawsuits, not the law itself).

There is something really important in these bills, though, and it’s this: politicians working to get anti-book ban bills passed are signaling to constituents that they are listening to library workers and that they care about what’s happening to libraries. They are championing the institutions being attacked. Even if their attempts are only moderately successful in addressing the issues, they’re majorly symbolic. These legislators are the ones that not only library workers should continue to get into the ears (and inboxes) of, but so, too, should every citizen concerned about what’s happening in libraries both in their state and beyond.

One thing we need to be conscious and considerate of, though, is where and how the future of the Leila Green Little, et al. v. Llano County, et al. case. Per the Fifth Circuit Court in its en banc ruling, there are no First Amendment rights in public libraries and thus, state-level laws hinging their freedom to read bills on this Constitutional amendment may be moot if this case makes its way to the Supreme Court. The three states under the Fifth Circuit jurisdiction–Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas–do not currently have any such legislation on the books.

2025 “Freedom to Read” Bills

Five states passed “Freedom to Read”/anti-book ban bills in 2025 so far.

Colorado

Bill: SB25-063 “Library Resource Decision Standards for Public Schools”

Addresses: Public School Libraries

This law applies to public school libraries statewide and it requires each school library have a written collection management policy. Books can only be removed from a collection if it is out of compliance with the policy (and doesn’t fall under routine weeding performed by a professional). The library’s policy must be made public, as much the titles being considered for removal. When a decision is made about removing a book, that decision must be made public as well.

Colorado’s bill also establishes protections for school library workers who refuse to remove books following a complaint.

This is Colorado’s second anti-book ban law. The first passed in 2024 and addresses public libraries. That law also requires clear, consistent collection policies and protects library workers who do not comply with demands to remove a book. It also includes a provision that outcomes of book challenges be made public, as well as names of those seeking to remove books.

Connecticut

Bill: S.B. 1271, “Freedom to Read” Bill

Addresses: Public Libraries and Public School Libraries

This robust bill offers a host of protections for library users and library workers and it applies to both public libraries and public school libraries. The bill requires clear collection policies that outline how books are selected, maintained, and removed, and it also emphasizes that no books can be removed for being “offensive.” Complaints about materials need to be backed up with professional and/or educational reasons.

Connecticut’s bill limits who can lodge complaints as well. Only town residents, parents, students, or school staff are allowed to challenge materials, and they have to do so formally in writing. Materials being challenged must remain available on shelves during the review process, and library workers are offered protections for not removing books when complaints arise.

This is also Connecticut’s second bill related to the freedom to read. Last year, Public Act No. 23-101–An Act Concerning the Mental, Physical, and Emotional Wellness of Children–made a pool of funds available for public libraries who meet a short list of criteria, including that they will not ban books.

New York

Bill: Assembly Bill 7777/Senate Bill 1099 “Freedom to Read” Act

Addresses: Public School Libraries

Public schools throughout the state of New York will have to have collection management policies that address what school libraries have on their shelves. This bill requires that the policies allow library workers the power to select and share materials that meet the needs and interests of all students being served.

The “Freedom to Read” Act was being presented simultaneously with the “Open Shelves” Act, Senate Bill 1100A, which did not make its way to the governor. The “Open Shelves” Act would have extended similar rights to library workers in public libraries, hospital libraries, and elsewhere, with explicit language around materials and programmings reflecting human rights and equal protection rights. This isn’t entirely off the table for the next legislative session.

Oregon

Bill: Senate Bill 1098

Addresses: Public Schools, including their libraries and classroom libraries

This bill limits who has the right to demand book removals from schools. Requests can only come from parents/guardians or employees of a school in writing, and materials cannot be removed from shelves until it goes through the formal review process. Materials pulled will need a written, publicly-available explanation as to why.

The bill further articulates that instructional material, textbooks, or library selections cannot be removed for reasons related to groups who are protected from discrimination, including people of color, LGBTQ+ people, disabled people, and others. In other words, the ideological reasons behind nearly every book ban in the US over the last four+ years are not grounds for material removal in Oregon public schools.

Rhode Island

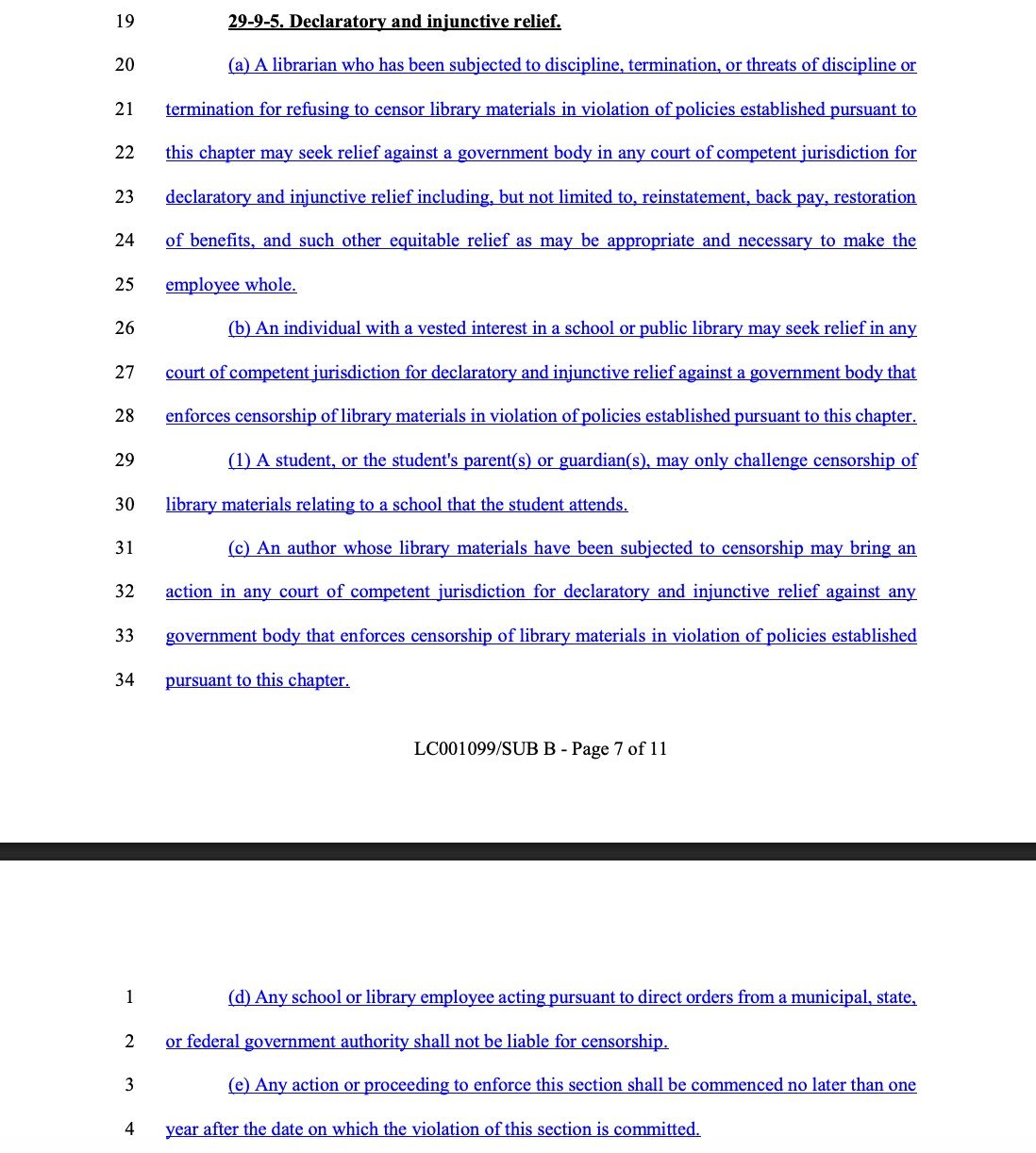

Bill: Senate Bill 238, “Freedom to Read” Act

Addresses: Public Libraries and Public School Libraries

One of the most heralded “Freedom to Read” laws to pass this year is Rhode Island’s. It is comprehensive, requiring that both school and public libraries develop and follow collection policies outlining what materials are available. There must be clear policies outlining how challenges work and the processes by which books are reviewed. The bill further provides protections for library workers from discrimination or punishment for not removing items upon request. The bill reaffirms the legal standard of the Miller Test–something that other states have tried to undermine in proposed legislation that drops the third part of the test, which outlines that materials are only obscene if they have no literary, political, scientific, artistic, or educational merit.

What makes Rhode Island’s “Freedom to Read” Act stand out from every other act passed so far is that it also guarantees protections for writers and for readers. They have the right to sue over censorship now, too.

This is, in many ways, the opposite of what parents have been provided in states like Idaho, where they can sue libraries over not removing books they deem inappropriate.

There are still “Freedom to Read”/”Anti-Book Ban” bills rolling through other state legislatures. Among them are Massachusetts and Delaware.

All of the States with “Anti-Book Ban” Bills Right Now

As of August 2025, the following states have all passed some form of “Freedom to Read”/Intellectual Freedom/Anti-Book Ban Bills:

*Moreover, none of these bills to date address the largest purveyor of book censorship, the prison system. As much as we need to fight for and on behalf of public schools and public libraries, so, too, do advocates for the freedom to read and freedom to think need to be advocating for those experiencing incarceration. Access to books and libraries reduces recidivism and has an incredible impact on those on the inside (see this, this, and this). Prison censorship is directly related to America’s legacy of slavery.

Book Censorship News: August 1, 2025

- Ohio lawmakers are looking for a way to override the governor’s veto of the provision in their budget that would require any and all LGBTQ+ books in public libraries to be out of sight of anyone under the age of 18. They’re this obsessed with genitals and gender.

- Remember how the book banners have said ad naseam that removing books from schools and libraries isn’t censorship because “you can just buy them!” Well, National Park gift shops might make purchasing inclusive books about slavery and the Civil War not an option–and it shouldn’t be shocking to hear this.

- Pinellas and Pasco County Schools (FL) have removed tons of books from their libraries because of how the state has threatened Hillsborough schools. Remember: Florida’s laws permit local level decision making in writing, but that doesn’t seem to be how it operates in reality. It’s the state making the calls.

- Last month, Harford County schools (MD) banned Flamer by Mike Curato. Recall: Maryland has an anti-book ban law applicable to public schools; these only matter as much as they’re enforced.

- There’s a stand off between the book banning arm of the South Carolina Board of Education and the Beaufort County School Board over what the process is for handling the flood of new book complaints from the state’s leading book banner.

- While we’re talking about South Carolina, the NAACP has filed a lawsuit over a provision in their budget related to classroom curriculum, as it has allowed for censorship of not just books but full courses (including an AP African Americans class).

- At least two Texas school districts have begun to develop their local parent groups who will decide which books are allowed in school libraries, per a new law. Pearland ISD is also prepping their pro-book banning, pro-parents make decisions, anti-librarians doing their jobs as skilled and educated professionals library policy.

- Corpus Christie Independent School District, also Texas, has started developing their “parents group to do the job of trained, educated professional library workers,” per the new state law. So, too, has Celina ISD.

- South Berwick, Maine, schools have not banned Molly’s Tuxedo, despite complaints over its content by national complainers.

- Despite the fact that residents of Huntington Beach *voted* to stop the city council’s book bans at the library, censorship is still happening because fascists don’t care about things like democracy.

- In Moscow, Russia, LGBTQ+ books and books about Ukraine are current censorship targets.

- Let’s stay international for the next couple of stories. First, Malaysia has banned two romance books. Second, Afghanistan has banned hundreds of titles nationwide.

- Nevada legislators passed two pro-library bills this session, but both were vetoed by the governor.

- Summer Boismier lost her teaching license in Oklahoma several years ago when she presented her students the QR code to access Brooklyn Public Library’s digital card and ebook collections. She says she’d do it again (GOOD).

- South Carolina Attorney General Alan Wilson is trying to get 17 states to ban “divisive” content from public schools. “Divisive” is, of course, anything not cishet, white, able-bodied, and male-focused. South Carolina already leads the US in state-sanctioned book bans.

- The New York ACLU chapter is investigating why the Eastport-South Manor school district disposed of hundreds of copies of 14 books, most of which have been targeted by banners nationwide.

- Grants Pass Public Schools (OR) have a new book policy which requires any new potential library books be posted “prominently” to allow the public

to make up reasons to ban themto view and books deemed “obscene, pervasively vulgar, or pornographic” are banned. No such books exist because no book available in public libraries or school libraries rises to the definition of obscene or pornographic, so it’ll be used to shove out LGBTQ+ books by the bigots. - St. Joseph School board members (MO) share how they were targeted and harassed by a big-money, far-right Christian organization in the state. Peep this lovely bit in the story: “This is the SJSD president showing exactly what she wants with the indoctrination of your children,” posted Kim Dragoo, a former school board candidate who was convicted of parading, demonstrating or picketing during the Jan. 6 U.S. Capitol insurrection. Dragoo was pardoned by President Donald Trump in January.”

- In Utah, students are now allowed to bring their personal copies of books banned across the state to school. This did not used to be the case–if the book was banned by the state, it was not allowed on campus in any capacity. Currently, Utah has 18 titles on its banned list.

- The Michigan Library Association is petitioning the governor to do more to protect books and libraries across the state.

- PEN America “filed a new legal brief Monday asking the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals to keep the injunction in place blocking Iowa’s ban on books that are not “age appropriate” from K-12 schools.”

- More progress is being made between the nonprofit Wisconsin Books to Prisoners and the state’s Department of Corrections when it comes to getting books inside prisons. Recall that prison censorship is the largest violation of the First Amendment nationwide.

- Lapeer District Library Board (MI) has moved their board meeting from 5:30 pm on the third Thursday of the month to 10 am, making it so folks who want to make clear book banning isn’t welcome can’t make it. You know, 10 am on a Thursday is a popular time for people not to be working. How all of these conservative board members have that time free is wild, isn’t it?

- State-level book banner Ryan Walters of Oklahoma was caught with explicit images at work on his work computer because for the far right, accusations are actually confessions. Remember he appointed the creator of that horrible Twitter account that has evoked plenty of stochastic terrorism to an important role in the state, too.

- New teachers to the state of Oklahoma will need to pass a PragerU-created test now that pushes “American exceptionalism” and anti-trans hate.

- “Shortly after a MAGA-aligned majority took control of Somerset County’s school board in last year’s election, they got to work. They passed a policy on what flags could be flown, attempted to usurp the superintendent’s decision-making power, and assumed control of decisions on which library books are purchased. Then they came for the school librarians. And that was too much.” This is the second such story in two weeks–this time we’re in Maryland. A reminder that for over 4 years, many have been warning that the goal is school board takeover to implement this nonsense. Don’t let it be too late.

Earlier this week, I covered the current state of the Institute of Museum and Library Services, including where it stands with the premature shutdown of the House of Representatives. Something that came up in that research was that there is also a potential budget cut for the Library of Congress. The status of that is also not yet determined.