Longtime readers will know that Science-Based Medicine (SBM) was originally proposed as an answer to what we view as the shortcomings of the evidence-based medicine (EBM) paradigm. Indeed, let’s go way, way back to the very beginning of this blog—January 1, 2008!—when co-founder Dr. Steve Novella announced the new blog and briefly described out what SBM is. I think it’s worth quoting again, all these years later, as a prelude to discussing how a new mantra that has arisen, “gold standard science,” that is in reality an anti-science buzzword cleverly disguised as support for the best science that seems on the surface even to echo some of our criticisms of the EBM paradigm. My “inspiration,” if you will, for this post were two very long screeds—so long, in fact, that they make my tendency towards logorrhea seem like the most economical use of language you can imagine!—by an antivaxxer named Toby Rogers. (Seriously, the first Substack I will address is close to 9,800 words, and the second is over 5,000 words, both not counting references.) I’ll have more to say about him later, but for now suffice to say that I’ve written about Toby Rogers a number of times although mainly on my not-so-super-secret other blog, and, unsurprisingly, he is now a fellow at the Brownstone Institute. The two Substacks by Rogers that I will be addressing include How Big Pharma hijacked Evidence-Based Medicine, Part I (subtitled Evidence-Based Medicine is not evidence-based nor medicine) and part 2, Seven philosophical criticisms of Evidence-Based Medicine and evidence hierarchies.

First, by way of comparison, let’s look at what Dr. Novella wrote about SBM and EBM in the very first post published on this blog:

Within the practice of medicine there is already a recognition of the need to raise the standards of evidence and the availability of the best evidence to the practitioner and the consumer – formalized in the movement known as evidence-based medicine (EBM). EBM is a vital and positive influence on the practice of medicine, but it has its limitations. Most relevant to this blog is the focus on clinical trial results to the exclusion of scientific plausibility. The focus on trial results (which, in the EBM lexicon, is what is meant by “evidence”) has its utility, but fails to properly deal with medical modalities that lie outside the scientific paradigm, or for which the scientific plausibility ranges from very little to nonexistent.

All of science describes the same reality, and therefore it must (if it is functioning properly) all be mutually compatible. Collectively, science builds one cumulative model of the natural world. This means we can make rational judgments about what is likely to be true based upon what is already well established. This does not necessarily equate to rejecting new ideas out-of-hand, but rather to adjusting the threshold of evidence required to establish a new claim based upon the prior scientific plausibility of the new claim. Failure to do so leads to conclusions and recommendations that are not reliable, and therefore medical practices that are not reliably safe and effective.

This is why the authors of this blog strongly advocate for science-based medicine – the use of the best scientific evidence available, in the light of our cumulative scientific knowledge from all relevant disciplines, in evaluating health claims, practices, and products.

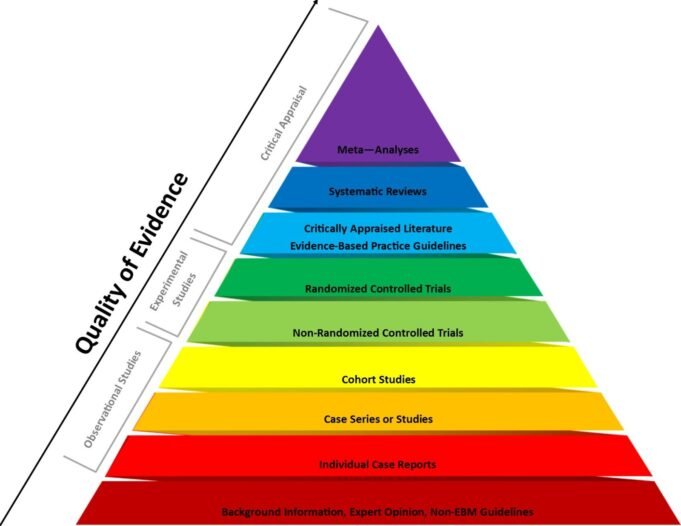

A number of our early posts started to put some meat on the bones of this concept, describing, for instance, how EBM as a paradigm for evaluating scientific evidence almost completely ignored—and, to a disturbing extent, still does—the concept of prior plausibility, thus allowing alternative medicine modalities whose precepts are, for all intents and purposes, physically impossible (e.g., homeopathy) to appear to have activity in the apex of single-study EBM levels of evidence (double-blind randomized controlled clinical trials, commonly abbreviated RCTs). Thus were deceptively justified abominations such as “integrative medicine,” quackademic medicine, and the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), formerly the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) over the last three decades. At the time, we advocated for a more Bayesian–based approach to RCT evidence that could take into account prior plausibility. Later, I started to discuss the ways that a hyper-strict reading of the EBM paradigm—which I like to refer to as “methodolatry,” or the “profane worship of the RCT as the only valid method of investigation”—had been increasingly weaponized by COVID-19 contrarians, pandemic minimizers, and antivaxxers to cast doubt upon vaccines and public health interventions, an approach that the antivax activist, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who is now Secretary of Health and Human Services, has continued under the guise of the administration’s buzzword “gold standard science.”

Reading Rogers’ screeds, one thing became apparent to me immediately. Whereas we at SBM have criticized EBM in order to strengthen the science behind medical tests and interventions and eliminate implausible treatments that do not work but can produce false positives in RCTs (e.g., homeopathy and acupuncture), Rogers’ purpose is very different. His criticisms of the shortcomings of EBM are not made as a prelude to trying to preserve the best of what EBM offers and to propose modifications to the EBM paradigm—as we have with the SBM paradigm—to strengthen the scientific evidence base undergirding our medical interventions. Rather, he is making these attacks to call into question what EBM tells us as a prelude to implying that his antivax ravings and quackery must therefore be taken seriously and that EBM is nothing more that a big pharma psyop to protect its hegemony and profits. It’s an old criticism of EBM, that it’s been “hijacked” by big pharma; indeed, John Ioannidis made just that claim nine years ago. Let’s just say that Rogers is no Ioannidis. (Sadly, these days Ioannidis is no Ioannidis any longer.)

Toby Rogers attacks EBM, part I

A superficial reading of Rogers’ first ten criticisms of EBM might lead the reader to think that there is substantial agreement between the SBM crew and Rogers. For instance, Rogers criticizes the evidence hierarchy used in EBM; so have we, for instance, the way that basic science evidence is placed near the very bottom of the EBM pyramid of evidence, when scientific plausibility needs to be a major consideration when considering various alternative medicine modalities. However, it doesn’t take long to see what Rogers is about. While our critique of EBM is basically that EBM is a good basic framework that works for a large percentage of cases (e.g., testing whether pharmaceutical drugs work or not), it is not enough and does not go far enough. Indeed, our key criticisms, again, boil down to:

- EBM’s lack of consideration of scientific prior plausibility, which can allow pure quackery to be portrayed by advocates of “integrative medicine” as “evidence-based”; e.g., homeopathy, acupuncture, and the like. Then advocates use RCTs that seem to show these modalities to be effective as a means of “integrating” quackery with real EBM, or, as Dr. Mark Crislip so famously put it, to “integrate” cow pie with apple pie.

- How some EBM fundamentalists (e.g., Dr. Vinay Prasad) have weaponized the status of RCTs at the top of the EBM pyramid to cast doubt on public health interventions that are not easily amenable to being studied by RCTs or for which RCTs would be unethical. The most famous example is RFK Jr.’s call for “double-blind” placebo controlled clinical trials of every vaccine on the childhood schedule, deceptively casting the lack thereof for some vaccines as evidence that they are dangerous—or, at the very least, inadequately studied—rather than as a result of its being unethical to randomize clinical trial subjects to a saline placebo control group when an effective vaccine exists.

Let’s compare the above to Rogers’ ten criticisms, which range from the seemingly reasonable to the more ideological:

- EBM has become hegemonic in ways that crowd out other valid forms of knowledge;

- Evidence hierarchies do not just sort data, they legitimate some forms of data and invalidate other forms of data;

- Meta-analyses and systematic reviews of RCTs are beset with epistemic problems;

- Most RCTs are designed to identify benefits but they are not the proper tool for identifying harms;

- RCTs are designed to address selection bias but other forms of bias remain;

- Case reports and observational studies are often just as accurate as RCTs;

- EBM is not based on evidence that it improves health outcomes;

- EBM and evidence hierarchies reflect authoritarian tendencies in medicine;

- Evidence hierarchies have reshaped the practice of medicine for the worse; and

- Evidence hierarchies objectify and/or overlook patients.

Ironically, #1 and #2 rather echo one of my criticisms, #2 more than #1, but Rogers is not about what we at SBM are about. Indeed, #8-#10—give the game away, in particular the lament that EBM and evidence hierarchies are “authoritarian” in nature and that EBM “objectifies” and/or “overlooks” patients, thus “reshaping the practice of medicine for the worse.” Shades of the “health freedom” movement! To put it explicitly, Rogers is not interested in making rational changes in order to build up the edifice of EBM to make the evidence base behind medicine stronger, he’s about tearing the edifice of EBM down, so that its walls have gaping holes in it, the better to let quackery and his antivax pseudoscience in. Indeed, one thing that I noticed immediately is that few of the articles that Rogers cites are less than a decade old, and many are more than two decades old. Thus, his arguments seem to be against an older, early version of EBM, as if EBM has never been updated. For example, he takes umbrage at arguments made in a 2004 commentary by Brendan M. Reilly, in which Reilly wrote:

Few would disown the EBM hypothesis — providing evidence-based clinical interventions will result in better outcomes for patients, on average, than providing non-evidence-based interventions. This remains hypothetical only because, as a general proposition, it cannot be proved empirically. But anyone in medicine today who does not believe it is in the wrong business

However, Reilly also wrote in the same commentary:

But it is the third essence of EBM—the process of practising it—that we understand least and spar about most. Many of us teach EBM (integrating best evidence with clinical expertise and patient values) knowing that it is nearly impossible to practise it in everyday clinical care.8–10This makes sense because someday practising EBM will be feasible—when technology for searching literature improves (soon) and when all of us are more EBM facile (not so soon). But we should not promote the practice of EBM until we know whether the process itself improves patients’ care. Improves? Compared with what? In our laudable compulsion to translate more and better research faster into clinical practice, we should keep in mind that mortality rates for many diseases have dropped dramatically in the past few decades—for example, a 50% decline in cardiovascular deaths in the United States.11 So someone must be doing something right. But who and how? The great irony about promoting the practice of EBM in the future is that we know so little about how clinicians practise medicine in the present.10,12 We need to find this out, if only to establish credible comparison groups for the experiments that must be done. When this research is done, one thing seems certain: at least some of us will feel good about the road we have taken.

Which is a lot more “gray” and less dogmatic than how Rogers portrays it as too “strident.” He prefers instead an argument made by D. M. Berwick in a 2005 commentary:

…we have overshot the mark. We have transformed the commitment to “evidence-based medicine” of a particular sort into an intellectual hegemony that can cost us dearly if we do not take stock and modify it. And because peer reviewed publication is the sine qua non of scientific discovery, it is arguably true that hegemony is exercised by the filter imposed by the publication process…

My first reaction was: Sir, you say this as though peer-reviewed publication being the main basis for what is accepted as scientifically supported in medicine were a bad thing. The ellipse at the end also led me to look up the commentary to see what Berwick wrote next, which was to refer to refer to an article in the same issue by Davidoff and Batalden. What was that article about? Basically, it was a lament that research into quality improvement (QI) was seldom published compared to science, along with reasons why and suggestions for improvement. For example, Davidoff and Batalden noted that many QI investigations could often fall prey to The Common Rule and be considered human subjects research and thus subject to institutional review board oversight and other onerous requirements that are arguably not necessary for research into improving processes of medical care rather than testing interventions. It’s a subject that I know a bit about, having spent several years involved in a statewide QI project designed to identify problems with breast cancer care and identify strategies to improve it. In other words, Davidoff and Batalden weren’t rejecting EBM; rather, they were proposing publication guidelines for QI research. Moreover, all QI research starts with evidence-based guidelines of care.

I could go on, but you get the point. Moving on to the second criticism, I could well have some sympathy for this point of view if I didn’t know what Rogers’ game was really about. I mean, seriously, I almost could have written this passage by Rogers:

Although EBM in the early years made reference to the totality of evidence, soon EBM became a way of excluding all studies except double-blind, randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) from the analysis. Stegenga (2014) writes: “The way that evidence hierarchies are usually applied is by simply ignoring evidence that is thought to be lower on the hierarchies and considering only evidence from RCTs (or meta-analyses of RCTs).”

Sound familiar? Yes, I myself (and others here at SBM) have criticized what I sometimes call “EBM fundamentalists” for their “methodolatry,” a term that I first discovered way back in 2009, and, once again, defined as the “profane worship of the randomized clinical trial as the only valid method of investigation.” Indeed, I’ve been noting the tendency towards methodolatry in EBM mavens dating back at least that far, ranging from prominent members of the Cochrane Collaborative, such as Tom Jefferson and Peter Gøtzsche, to famous scientists like John Ioannidis, to, of course, COVID-19 contrarians like Vinay “RCT or STFU” Prasad. In his other Substack article, Rogers even echoes our earlier criticism of EBM’s blind spot towards basic science evidence. (More on that later.) I had to ask: Am I dreaming? Have I gone mad? An antivax and transphobic advocate for quackery just wrote something that I might have written! Interestingly, though, he doesn’t really expound upon the theme, other than to quote a couple articles from 2005 and 2014. Moreover, if Rogers were really about criticizing methodolatry and EBM fundamentalism “excluding” all studies other than double-blind placebo-controlled RCTs, you might think he’d have a problem with RFK Jr.’s call for studying every vaccine on the current schedule in an RCT versus saline placebo. If he has made such a criticism, I haven’t found it, but I have found his praise for RFK Jr., enough to have been a regular contributor for a time to RFK Jr.’s antivax org Children’s Health Defense.

Of course, Rogers also attacks meta-analyses. Once again, as we have said here at SBM more times than I can remember, when it comes to meta-analyses, “garbage in = garbage out” (GIGO). No one denies that meta-analyses can be biased, but Rogers’ discussion relies on, once again, old publications, many of which date back to before PRISMA guidelines were first published. PRISMA guidelines, recall, were formulated to minimize or eliminate many of the biases that Rogers discusses. Since then, PRISMA guidelines have been continually updated, with the most recent version being PRISMA 2020 and most journals requiring systematic reviews and meta-analyses to follow PRISMA guidelines. Rogers might have a point when he states:

It is not that subjectivity itself is necessarily a problem. The subjective wisdom that comes from years of experience could be quite helpful in evaluating the evidence. The problem with meta-analyses as currently practiced is that those involved usually do not acknowledge their own subjectivity while simultaneously excluding the sort of reasoned subjective analysis (from doctors, patients, or perhaps even philosophers) that might be helpful.

However, once again, notice how he calls for more “subjective analysis,” rather than efforts like PRISMA to make meta-analyses more objective. One can’t help but acknowledge that no effort of human beings can ever be totally objective or free from subjective influences, but what Rogers is calling for is not greater rigor, but more of a window to allow subjectivity in. Basically, he wants to replace what he sees as the influence of big pharma with the influence of people like him, and I know his history with respect to science and vaccines.

The same is true regarding #5. Yes, RCTs are best at minimizing selection biases, and, yes, RCTs can have other biases. Perhaps the most telling part is this:

So simply controlling for selection bias is not sufficient to guarantee scientific integrity. Furthermore, it is not even clear that RCTs as currently practiced actually prevent selection bias:

A research group conducted a systematic review of 107 RCTs about a particular medical intervention, using three popular QATs (Quality Assessment Tools) (Hartling et al. 2011). This group found that allocation concealment was unclear in 85% of these RCTs, and that the vast majority of the RCTs were at high risk of bias. Another group randomly selected eleven meta-analyses involving 127 RCTs on medical interventions in various health domains (Moher et al. 1998). This group assessed the quality of the 127 RCTs using QATs, and found the overall quality to be low: only 15% reported the method of randomization, and even fewer showed that subject allocation was concealed (Stegenga, 2015).

Perhaps the authors of these studies were simply careless in describing their methods. But given that directors of Contract Research Organizations boast of their ability to deliver the results desired by their clients (Petryna, 2007 in Mirowski, 2011) it seems reasonable to wonder whether double-blind randomization is actually happening at all in some clinical trials that purport to be RCTs.

I would counter with a different take on this problem and argue this: The problem, as related by Rogers, is not with RCTs per se, although he wants to make you think that it is. Rather, the problem is that all too often we as a community of physicians and scientists do not carry out and report RCTs in a sufficiently rigorous fashion and that perhaps greater oversight is required over CROs. After all, the reason that pharmaceutical companies hire CROs is because CROs can allow them to open a clinical trial in many locations and allow them to contract out the work of actually recruiting subjects and running the actual trials that they’ve designed in consultation with the FDA. Again, it is telling that Rogers doesn’t suggest any strategies to correct this perceived problem. He only enumerates the problem in order to cast doubt on the findings of EBM based on RCTs.

The same thing is true of #6, which notes that case reports “and observational studies are often just as accurate as RCTs.” Of course, in this case, the word “often” is doing a lot of heavy lifting here, but never let it be said that Toby Rogers was ever in any way constrained by complexity or an obligation to look at a question more holistically. For instance, to ask whether case reports are as accurate as RCTs, Rogers dips way, way back to a study from 1982, where the investigators looked at 52 first reports of adverse reactions to drugs, following up 18 years later to see if the adverse reactions were validated as having been due to the drug suspected in larger studies, noting that 75% of the adverse reactions were later confirmed in additional studies as having been due to the drug. This then leads Rogers to opine:

When one compares the 75% success rate of anecdotal first reports with the fact that 75-80% of the most widely cited cancer RCTs cannot be replicated (Prinz, Schlange, and Asadullah, 2011; Begley and Ellis, 2012), the decision to place RCTs at the top of the CEBM evidence hierarchy, while denigrating case series, appears unwarranted.

This is totally a bait-and-switch, because the articles cited do not answer the question of the reliability of RCTs. For example, Prinz et al is a study looking at preclinical studies identifying molecular targets for drugs and has nothing to do with clinical trials. It looked at preclinical drug discovery in cell culture and animal models; it’s about “wet lab” science, not clinical science, as the authors themselves write. Similarly, the title of the Begley and Ellis article tells you what it’s about, namely, Raise standards for preclinical cancer research. It’s basically the same message, that a lot of preclinical science, warning glumly that the “inability of industry and clinical trials to validate results from the majority of publications on potential therapeutic targets suggests a general, systemic problem.” In other words, both papers are about the difficulty and lack of reproducibility translating preclinical science into actual cancer therapies; these articles have nothing to say about the reliability of RCTs compared to observational studies. Nice try, Toby. You thought no one would actually look up your references and read them.

But coming back to the question of whether observational studies versus RCTs, Rogers actually cites a paper that points out that it’s far to simplistic a question to ask if, in general, whether observational studies can be as accurate as RCTs. As noted by Bosdriesz et al in 2020, who in a review of this very question concluded, quite reasonably:

The answer to the question “is an observational study better than an RCT?” depends on the research question at hand. There is not one overall gold standard study design for clinical research. With respect to analytic studies, the RCT is the best study design when it comes to evaluating the intended effect of an intervention. However, this type of research represents only a fraction of all clinical research. Observational analytic studies are most suitable if randomization of the intervention or exposure is not feasible or if the research question focuses on unintended effects of interventions. For non‐analytic or descriptive studies, observational study designs are also needed. We conclude that RCT and observational studies are inherently different, and each have their own strengths and weaknesses depending on the study question.

Rogers take on the article? This:

In 2017, Thomas Frieden, the former Director of the CDC, made the case in the New England Journal of Medicine that a wide range of different study types can have a positive impact on patients and policy. He makes the simple point that each type of study has strengths and weaknesses and the study type should match the type of problem the researchers are trying to address. He points out that alternative data sources are “sometimes superior” to RCTs.

So a wide range of different types of evidence can be valid and help inform clinical decision-making and yet the current practice of EBM systematically excludes everything other than the large RCTs favored by pharmaceutical companies.

No one other than EBM fundamentalists—and perhaps not even EBM fundamentalists—argues that we shouldn’t evaluate a range of different types of evidence. Remember that the EBM paradigm is about ranking the relative strength and reliability of different forms of evidence, not excluding them; at least, that’s how it’s supposed to work. Again, given what Rogers is arguing, one might think that he’s unhappy with the “gold standard science” being touted at HHS that supposedly mirrors Dr. Prasad’s longstanding (at least since the pandemic and only about public health) “RCT or STFU” ethos.

I also can’t help but be amused a bit at #4, namely that “RCTs are designed to identify benefits but they are not the proper tool for identifying harms.” That’s not entirely true. RCTs are a perfectly acceptable tool to identify harms. Every RCT that I read reports the rate of adverse events in the control and experimental arms and assesses whether there are specific adverse events that are more common in the treatment group. The problem with RCTs with respect to identifying harms is not that they can’t identify harms. It’s that they are not good tools for identifying rare harms, mainly because there are usually not enough subjects in each group to detect statistically significant differences in such uncommon harms. That’s why pharmacovigilance programs exist.

I will concede that Rogers has a point when he notes that “FDA post-market surveillance is under-funded by design and not sufficiently staffed to respond to the size of the task,” except that I don’t think it’s by design or intent. It’s more as a result of neglect and politics. It’s because the FDA has long been underfunded for all its activities, a situation that is about to become very much worse. If Rogers is really concerned about post-licensure surveillance of, for instance, vaccines, he should be outraged at the massive budget cuts aimed at the FDA for fiscal year 2026. If he has expressed such outrage, I have yet to see it. Maybe a reader could clue me in.

Oh, wait. Maybe not:

How do we know they’re fraudulent? Rogers doesn’t say, other than to say:

Everyone knows that they are fraudulent (even though the mainstream medical profession tries to excuse this fraud). In clinical trials for vaccines, the control group is not given an inert saline placebo and is given another toxic vaccine or the toxic adjuvants from the trial vaccine instead. The Informed Consent Action Network (2023) has the receipts.

But wait. I thought that Rogers’ complaint was that EBM was too hidebound and too dogmatic in demanding RCTs über alles. I’m so confused. Of course, Rogers’ real game is painfully obvious. He doesn’t like EBM because he thinks all the RCTs on vaccines that demonstrate their safety and efficacy are “fraudulent. Ditto the RCTs for drugs that he doesn’t like, such as psychiatric drugs and statins. Let’s just say that, as a scientist, physician, and/or clinical trialist, Rogers is a political economist.

The remaining complaints against EBM are pretty standard quack complaints about conventional medicine in general, particularly the claim that EBM is authoritarianism. At this point, I was getting similar vibes that I got nearly two decades ago when I first encountered quacks arguing against EBM by calling those who demand EBM, specifically the Cochrane Collaboration, “microfascists,” to which I added that they must also be wearing micro-brown shirts and black boots and carrying micro-truncheons. Rogers also complains that pharmaceutical companies use EBM to sell their products, to which I responded: Damn those evil pharma companies, selling their products by touting that they had been shown to be safe and effective in RCTs! Those bastards!

Naturally, Rogers can’t resist a bit of a conspiracy theory. He notes how N-of-1 trials (trials of a single patient observed before and after an intervention) were in 2002 proposed to be at the top of the evidence hierarchy by the American Medical Association (AMA). However, over the next 13 years, N-of-1 trials kept falling down the ladder of the evidence hierarchy, so that by 2015, the AMA had fully embraced Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) as the system for ranking strength of evidence:

The third edition of The Users’ Guide to the Medical Literature published in 2015 fully embraces GRADE as the AMA’s preferred framework for making prevention and treatment decisions.

I saw GRADE in use when I watched every meeting the FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) and the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) in 2022 and 2023. GRADE is a tool to give legitimacy to ANY medical intervention no matter how abysmal the data.

And:

So within 13 years (from the first edition in 2002 to the third edition in 2015) the AMA went from the best-in-class evidence hierarchy that acknowledged individual difference to a cartoonish monstrosity, GRADE, that is just a tool for laundering bad data on behalf of the pharmaceutical industry. In the process the AMA sold out the doctors in their association and the patients in their care to the drug makers.

There you have it, the real reason why Rogers detests GRADE and the trappings of EBM; they were the basis for approving COVID-19 vaccines, and they are at the basis of all the clinical data showing that vaccines are safe and effective.

Rogers goes Bayesian and basic science?

As I said above, it both alarms and amuses me that Rogers could write things that sound like something I might have written, even if it’s only short passages of a paragraph or two. For example, in his second Substack on the topic, he writes:

This inferential gap is unlikely to ever be bridged because there is infinite variety in the human population so responses to medical interventions will always vary as well. Bayesian statistics might help narrow the gap a bit (see next section) as it allows one to continually refine estimates as new evidence becomes available (conditional probabilities that affect the prior probability of the hypothesis). But even with Bayesian statistics, the best one can come up with are probabilities, not the deterministic thinking of EBM. These are extraordinary debates at the core of the philosophy of medicine — and it is exactly these sorts of debates that EBM proponents circumvent in making RCTs the sole tool for clinical decisions.

As I discussed earlier in this post, a key component of SBM, which is to us an enhancement of EBM, is the use of Bayesian inference, which requires an estimate of prior probability. In other words, when doing an RCT, one needs an estimate based on existing evidence of what the probability is that there will be a significant difference between the control group and the treatment group. Our point was not so much to argue over fine differences in prior probability but rather to point out that, for modalities that are physically impossible, like homeopathy, the prior probability is very close to zero, if not for all intents and purposes indistinguishable from zero. The consequence of such reasoning is that there are some treatments that can be rejected on the basis of basic science alone and that for treatments with an incredibly low prior probability truly extraordinary evidence of efficacy would be needed to accept them.

Rogers misleading portrays the battle between frequentist statistics and Bayesian reasoning as the sole reason why RCTs rule. Yet there is no reason why Bayesian statistics can’t be used to design clinical trials and analyze their results. Indeed, this has been proposed by simply coming up with a table over what p-value should indicate statistical significance in an RCT based on the estimated prior probability, with lower prior probability hypotheses requiring a much lower p-value to be considered significant, a Bayesian correction, if you will. The real tricky part is coming up with a reasonable estimate of prior probabilities.

Now here was the disturbing passage, if only because it sounds as though it could have been written by yours truly:

Several authors have noted that EBM tends to overlook and ignore the contributions of basic science (also called “bench” or “fundamental” science and I will use these three terms synonymously in this section). Bench research is defined as “any research done in a controlled laboratory setting using nonhuman subjects. The focus is on understanding cellular and molecular mechanisms that underlie a disease or disease process” (“Bench research”, n.d.). Merriam Webster’s Dictionary defines basic science as, “any one of the sciences (such as anatomy, physiology, bacteriology, pathology, or biochemistry) fundamental to the study of medicine” (“basic science”, n.d.).

The CEBM evidence hierarchy lists basic science as the fifth level of evidence, below the threshold suggested by Strauss et al. (2005) and others as even worth reading. To be clear, the CEBM and other evidence hierarchies are not excluding bench science entirely from the study of medicine — they are proscribing the consideration of bench science by doctors when they make clinical decisions (presumably others, namely pharmaceutical companies and academic researchers would be free to continue with a more comprehensive approach). Excluding basic science in this way is an odd choice because basic science has always been an essential component of establishing causation.

Even as much as this sounds disturbingly like what we’ve argued here on SBM, there are enough “tells” to let you know that Rogers is going in a much different directions. (It also wouldn’t surprise me if the “several authors” referred to above include Steve Novella, Kimball Atwood, and myself, all of whom have written on this topic, including in the peer-reviewed biomedical literature. In any case, Rogers continues:

Goldenberg (2009) argues that the degradation of pathophysiology in evidence hierarchies is unwarranted “as pathophysiology often provides more fundamental understanding of causation and is in no way scientifically inferior” (p. 180).

La Caze (2011) voices alarm that evidence hierarchies overlook the contributions of basic science. As pointed out above, basic science is usually assigned to the lower tiers of evidence hierarchies. While the assignments to the different tiers are rationalized based on reference to “quality” in fact, “proponents of EBM provide little justification for placing basic science so low in EBM’s hierarchy” (La Caze, 2011, p. 96). “Proponents of EBM urge clinicians to base decisions on the outcomes of large randomised studies rather than the mechanistic understanding of pharmacology and physiology provided by basic science” (La Caze, 2011, p. 83).

Again, when we at SBM invoke basic science, we tend to invoke it in a negative way, where certain modalities that are physically impossible or so close to impossible as to be indistinguishable from it (e.g., homeopathy) can be rejected solely on their violating the laws of physics and where modalities that are incredibly improbable (e.g., acupuncture) require extraordinary evidence to overcome their near-zero prior probabilities. I suspect that what Rogers is signaling is approval of “autism biomed” quackery, which often treats autism based on dubious biochemical mechanisms that its practitioners apply to the condition of autism whether they are relevant to the disorder or not. He might also be making a nod to “functional medicine,” which worships “biochemical individuality” as an excuse to justify a clinician doing whatever they want, regardless if it’s science- or evidence-based or not.

What this is really about

What Rogers is about has little or nothing to do with strengthening the scientific basis of medicine or improving medicine care. Rather, it’s about giving quacks and antivaxxers cover under the guise of science to do whatever they were going to do anyway. To show this, it’s helpful to quote the last passage in each of Rogers’ Substacks.

From part I:

We know that EBM is a fraud because it ranks rigged corporate studies ahead of the paradigm-shifting breakthroughs discovered by parents that are actually helping autistic children.

Remember Jenny McCarthy referring to her son whose autism she blamed on vaccines, saying “Evan is my science”? That’s what Rogers wants. Also:

Going forward, any system of medicine in connection with autism must start with the individual child and his/her family as the highest form of evidence (because obviously they are). All forms of data, no matter how unconventional or “outside the box,” must be brought to bear on supporting recovery and preventing this injury from happening to others. Rigged corporate RCTs have no place in actual medicine; their only appropriate use is as evidence of crimes against humanity in future Nuremberg trials of pharmaceutical executives and their enablers in government. The revolution we seek is thus a return to actual science instead of the genocidal corporate nonsense posing as evidence-based medicine today.

Wow. Rogers is an angry dude who hates EBM. Don’t believe me? Here’s the conclusion of his second Substack, or part 2:

The history of EBM reads like a Greek tragedy. A bunch of smart, seemingly well-intentioned people organized themselves to take over the practice of medicine. They wanted to make it better. It went well for a while but then hubris, greed, power, and corruption took over. Epidemiologists became a new priestly class and replaced science with dogmatism. Once unleashed, EBM became a runaway freight train. Now it is actively harming patients and destroying allopathic medicine in the name of saving it.

We need not sacrifice our dignity, common sense, and rational faculties on the altar of EBM as Guyatt and others have done. Rigged RCTs are not evidence. Corporate science is not science. We need to return to the old ways. We must let doctors be doctors again, relying on evidence, experience, and intuition — phronesis as Aristotle taught us (and Kathryn Montgomery reminds us). And we must let parents be parents again. Personal sovereignty and responsibility are the foundation of medicine and society. No financially conflicted epidemiologist in an ivory tower thousands of miles away (or heaven help us, Washington D.C.) knows what’s best for a person. The era of corporate EBM is over and the future of medicine is decentralized, N-of-1, non-corporate, non-government, person-to-person, direct primary care, based on the totality of evidence, decency, life experience, dialogue, and personal values.

Does the term “actual science” remind you of RFK Jr.’s and cronies’ parroting the term “gold standard science.” It should. It’s the same concept in a different form. Of course, while RFK Jr. and his acolytes like Vinay Prasad and Marty Makary like to imply that this “gold standard science” involves the most rigorous application of the EBM paradigm, up to and including saline placebo-controlled RCTs of every vaccine on the childhood vaccination schedule, when it comes to interventions and quackery that RFK Jr. tends to like, that “gold standard science” eagerly embraces a “more fluid” concept of evidence.

That is what Rogers is really embracing. Not “actual science.” Not a the actual meaning that real scientists would take from the term “gold standard science.” Rather, he wants to base medicine on any form of science and evidence that confirms what he already believes, namely that vaccines cause autism, are ineffective, and are downright dangerous. He wants to base medicine on whatever bias-prone personal observations that parents or quacks have regarding autistic children or any other person with a medical condition. Any other form of evidence is to him “rigged” or “corporate.”

Far be it from me to deny that there are problems with the EBM paradigm. After all, I’ve written about the problems that I perceive with EBM for over 17 years now. The difference between my criticisms and Rogers’ criticisms is that mine are grounded in actual science (if you’ll excuse my appropriation of the term), while Rogers are designed to let quacks find whatever “evidence” they need to ply the quackery that they were going to ply anyway, just now with seeming “science” behind it.